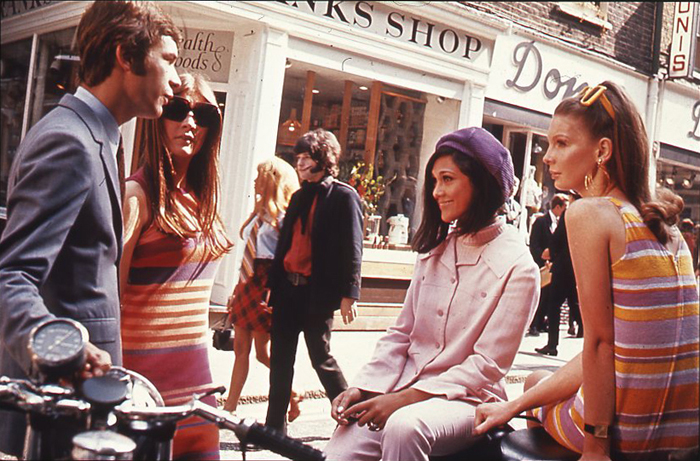

Buying clothing can be fun: the visceral thrill of all the new colors and textures; the gratification of clerks catering to your whims; the way a garment can make you feel like a different person.

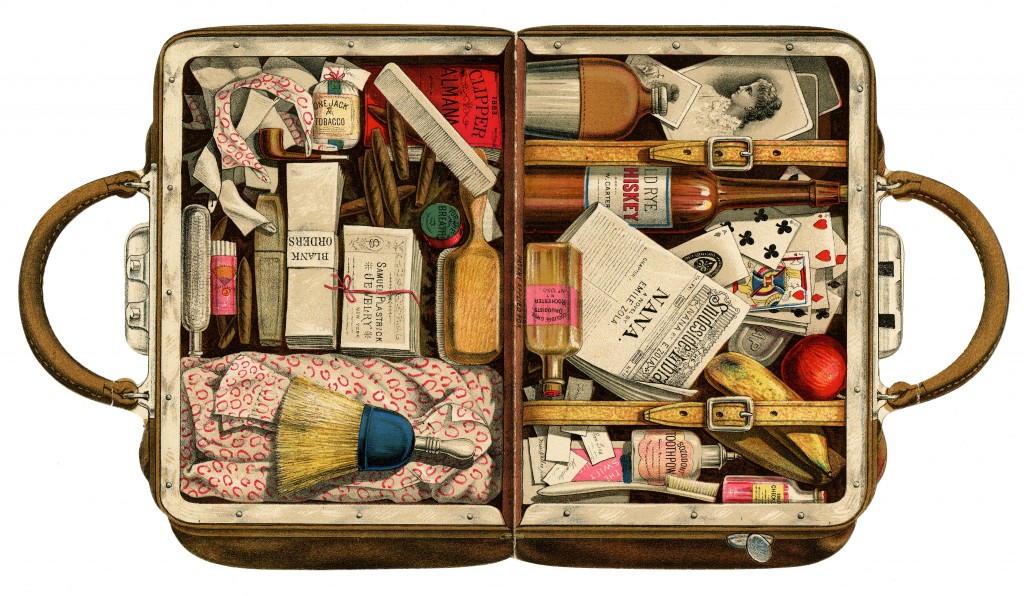

Beyond this, clothing is a drag. It’s dissatisfying, as garments rarely look as good in your closet as they do on display. It’s also time-intensive: trying to get one’s pants and shirt to “work” together; burrowing through closets in search of some lost item; or, worrying about whether one’s wardrobe might appear dated.

Cultural norms make this even more inconvenient. We find ourselves contemplating whether we’re under or overdressed, and forced to comply with stifling office dress codes. For a species that considers itself evolved, we sure do worry a lot about inconsequential details.

Clothing is not a representation of one’s success, professionalism, or capability; yet, we fail to treat garments for what they are: a layer of protection from the elements. Perhaps it’s time for us to align our behavior with what we all intrinsically know.

Yes, people do make assumptions based on our visual presentation. This doesn’t need to make us succumb to social pressures. Instead, we simply have to seek out clothing that is deliberately plain and unremarkable. By this, I mean basic garments that are as timeless as possible. Doing so will allow you to blend, and when it comes to dress, this is a good thing. (Should you wish to stand out from the crowd, consider doing so with your intellect, actions, or humor.)

By treating clothing simply for what it is, you are one step closer to eliminating a substantial chunk of mundanity from your life. This will subsequently open up time for more interesting and useful pursuits. It will also keep your closets from overflowing with embarrassing fashion missteps.

Notes:

Some (e.g. police officers) are forced to wear uniforms due to their work. This probably won’t change, but they can apply the above when away from work.