“Sure, I often have lunch/wine at the On Loc around 2:30 PM.” This is the response I get to my email with the subject line: “Want to talk about the Valley of the Headhunters with me?” (For the record, we spend very little of our lunch on that topic.)

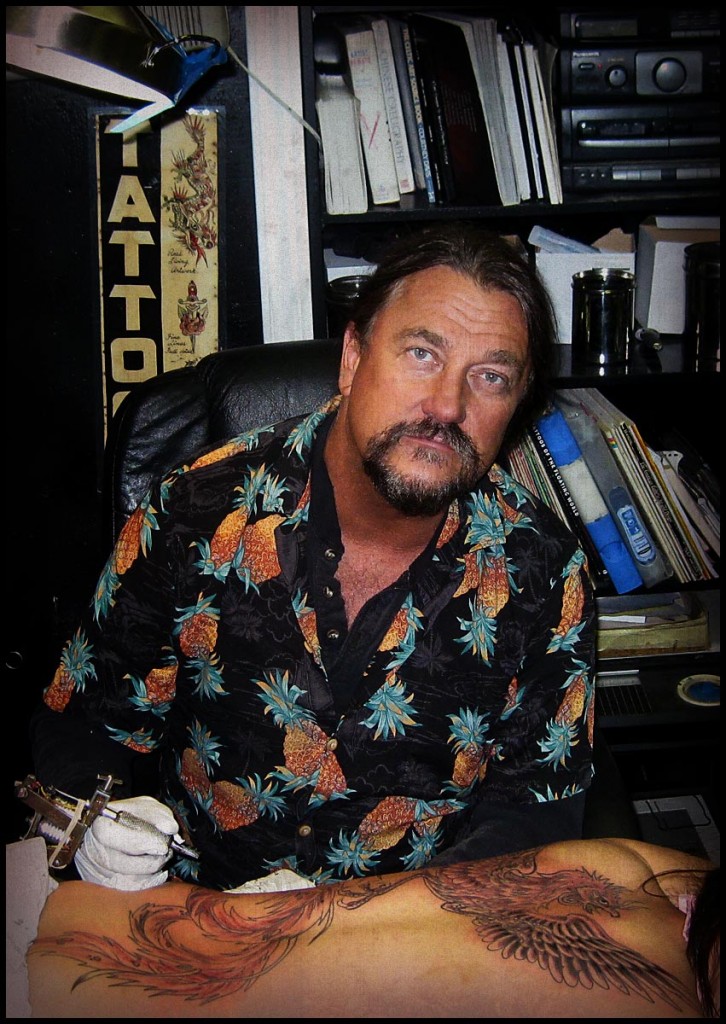

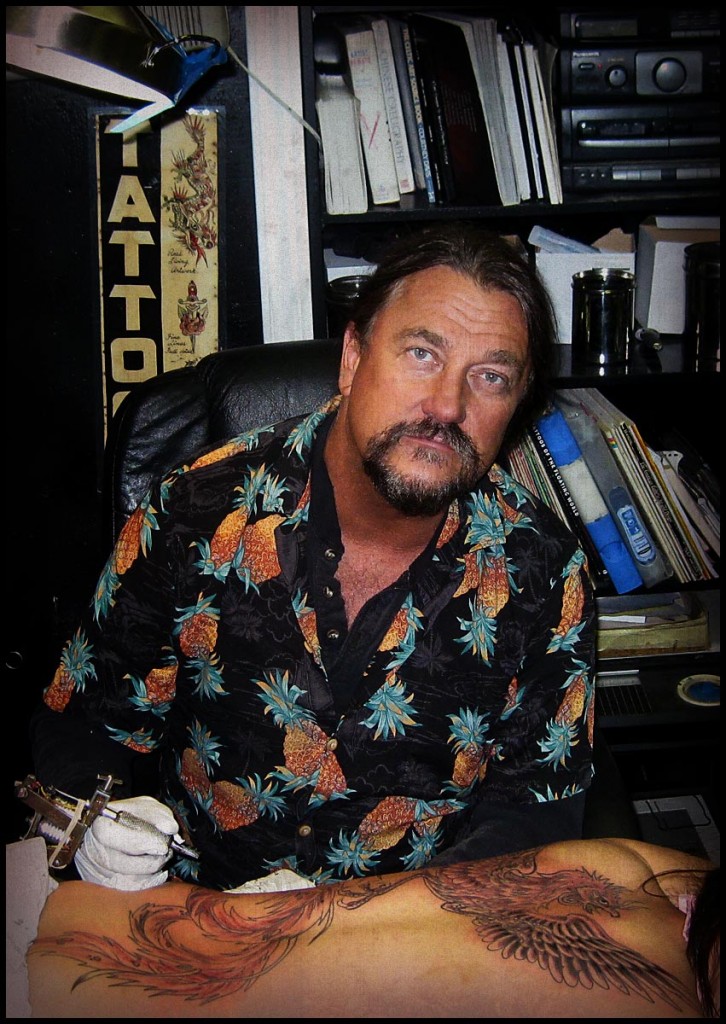

Photography Advice at the Tattoo Shop

This is the second time I’ve met Thomas Lockhart. The first is when I’m 18, and in art school. I want to document what goes on in a tattoo shop, and find West Coast Tattoo in the Yellow Pages. I walk in sheepishly with a few rolls of film, my crackling post-pubescent voice, and a dreadful mullet. I then do my best to take a few photos without upsetting anyone—I’m a scrawny kid next to these hardcore seeming dudes, and I really don’t want to piss anyone off.

I wrap up quickly and thank Thomas for his time. He looks up from his work, perplexed. “That’s it? Aren’t you going to bracket your shots? At least I did that when I was in school.” This moment has stuck with me for a long time. It’s funny, and saps the tension I’m feeling, from the air. Over the following years, I often wonder what has become of this fellow.

For most of my life, I’ve felt like a fraud. There’s never been a time when I believed I understood enough to get past the starting line; moreover, I’ve always imagined myself to be the human embodiment of the word, vanilla. While I’ve aspired to live a bold, adventurous life, I’ve mostly found myself smack dab in the mainstream. My aspirations and actions are disconnected.

This may be why I’m anxious in meeting Thomas Lockhart. I’m bad with people—particularly those I admire. And Thomas is one of these. To me, he seems like an original: he does his own thing, free of the constraints most of us put on ourselves. He’s touched foot on every corner of the planet, hobnobs with local glitterati (even if he doesn’t look the part), and seems to be moving to his own personal rhythm.

Psychology Major; Aviator; Tattoo Artist

My day has turned into a bit of a shitstorm, which leaves me rushing to catch a cab in order to make it across town. Somehow it works out, and I arrive at the restaurant right on time. This is when I come to realize just how unprepared I am. You see, writing isn’t my day job, but rather a bit of a hobby. Real work needed to take priority over the past week, and I’m not caught up on my research for today. Worse yet, I realize that I have left my note pad at the office. Thankfully, I have a record function on my smartphone. I just hope my subject isn’t too irritated at how unprofessionally I’m treating this whole thing.

I watch Lockhart approach the restaurant, but he fails to make his way to the table. After a few moments of waiting, I walk over to find him examining the menu on the wall. He has no idea who I am, so, I explain that we had an interview planned for today. He’s caught off guard, having forgotten about our meeting entirely, but agrees to sit down and talk.

Thomas grows up in Pender Harbour, on British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast. At six years old, he’s exposed to religion for the first time. His mother, a school-teacher, thinks Sunday School is a good idea, so, she sends him to the local tabernacle. This prompts him to ask bigger questions of her, like: where do we come from? She presents notions of the big bang theory, and evolution, which he determines are much more plausible than what he hears from the minister across the street. Religion becomes a central theme in our discussion. It’s roots, impacts, and sometimes apparent lunacy.

Upon his parents’ divorce, he moves to Saskatoon with his mother. This is before making his way across the country to study art and psychology at Ottawa’s Carleton University. He then travels to Argentina, training at the Aviation Academy. This vocation, however, comes at odds with his outward appearance. Those hiring pilots aren’t that thrilled with the notion of employing those with ink under their skin, long hair, and piercings.

Worried that this can only lead to a life that, as Lockhart describes it, will be a “holding pattern,” he makes a rapid exit, seeking something a little more “congenial.” A 26-year-old Lockhart attends a convention, put on by renowned tattoo artist Dave Yurkew, and something clicks. “Up at the crack of noon, hustling women, meeting interesting people, and downing a beer or two along the way seemed a much more civilized way to live my life,” he explains.

“So, You’re Making Documentaries?”

I’m not an interviewer and this becomes apparent painfully quickly. Thomas isn’t really that sure what Deliberatism is about, and I find myself incapable of articulating our purpose accurately—or, for that matter, coherently. (For a moment, he confuses me for a documentarian.) Little of this seems to matter much, though, as he seems far more interested in helping me find a place to travel to, than telling his story.

“Young kids? You need to go to Vietnam! Great food… It’s a fusion of Chinese, and crepes, and sauces! You’d have fun there, and it’s cheap. Very progressive.” He talks about how affordable hotels are, and the beautiful conservation areas there. I then mention that someone I once worked with had written glowingly about her travels in Bali. He becomes alive, nearly poking me in the eye with his finger, out of pure exuberance, “That’s it—Bali! Yes. It’s a jewel—a jewel!”

Eventually, he seems to understand what our project is about, but I don’t know that he completely can. I want to quote Thoreau’s comment about men leading “lives of quiet desperation,” which I’m sure he’ll recognize, but I doubt he’ll properly understand. I don’t think he’s worried about retirement, what his neighbors are doing, or, whether his shoes and belt match. These things that so many mainstreamers fret about, seem a million miles from his world.

We end up on a tangent, followed by another, and yet another; when he pauses for a moment and asks me what we were talking about. This is what a conversation with Thomas is like: we bounce from tales a biker pulling teeth from a corpse, to the ethics of vegetarianism, to how he broke his back in the mountains… all as though these topics are no big deal. I get the feeling that Thomas believes these are the same things others chat about over Sunday brunch.

A Love Affair with Tattoos

“Back then, there was no training,” Lockhart explains about the early days of tattooing in Vancouver. He notes that it was so hard to get access to machines that most people would just make their own. “I was using guitar strings and doorbell buzzers; I didn’t know what the fuck was going on.” He eventually gets access to a proper machine. (You can now buy these online for as little as $10.)

Even a little research into the world of tattoos shows just how much things have changed over the past decades. One of the first tattoo conventions, for example, was initially looked upon as a looming disaster. Michael Yurkew (son of the renowned Dave Yurkew) recounts the worry that attendees, “might kill each other if they’re all in the same room.” Artists, at the time, were more secretive about their work, than those we now see on reality television.

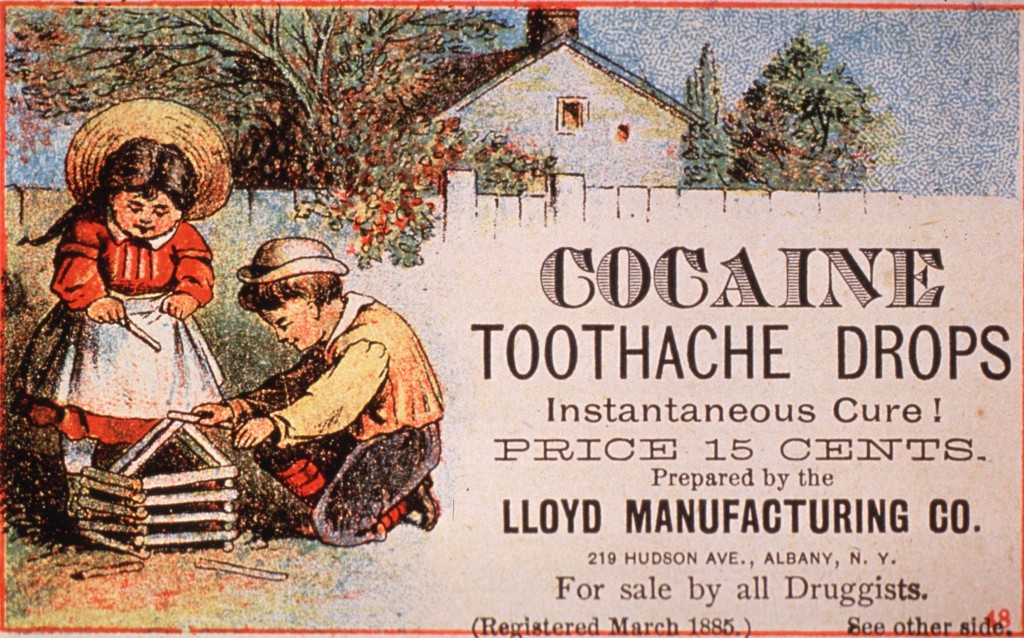

Lockhart goes on to explain that tattooing in Vancouver essentially started in the 1890s. He personally learns this through the help of Lyle Tuttle, who he considers to be the grandfather of present day tattooing. Tuttle sends Lockhart a card from a chest full of artifacts, referencing a tattooist named Professor George Johnson. (At the time, tattoo artists use prefixes like “Doc” and “Professor” to connote a kind of legitimacy—which sometimes wasn’t warranted.) It takes him years, but he follows this link to Japan, through to Vancouver, and eventually down to New York. He starts to connect the different artists of the time, even learning that the first electric tattoo gun in Vancouver was in use in the late 1800s.

The stories weave in and out, and I have a hard time keeping up. The names he mentions are mostly foreign to me, as I don’t know anything about the art form. (This might change when Thomas publishes the book he’s completing on this topic.) His opinions and stories are numerous. Some bum him out, while others quickly lead to boisterous laughter.

He talks about how a group of artists would design work and then ship the associated acetate to their colleagues. These were intended as an act of goodwill, amongst friends. They would then share credit, noting both who designed the piece and who inked it. Lockhart seems disappointed by Ed Hardy. He explains that Ed put these shared images on t-shirts and cashed in on them with little mention of the others’ involvement.

This doesn’t affect his admiration for Hardy, who inked part of Thomas’ body, though. He acknowledges that he’s a great talent, recounting that Hardy can simply start creating, without a rigid plan, and masterfully produce beautiful art. He notes that while many young artists think they can mimic this process, few can make it happen—because, “they want to be Ed Hardy, but they’re not Ed Hardy.”

Lockhart recounts a story, of how Hardy put him in touch with fellow artist Zeke Owen. In it, Thomas travels to North Carolina by bus connect with him, only to find himself in the middle of nowhere—a “cultural wasteland.” Marines roll in on weekends flush with cash, but with little to do. Many elect to watch strippers, frequent prostitutes, and get tattoos. In spite of how dreary it may seem, Thomas quickly learns how profitable this setup can be. Zeke opens his shop at 4:00 in the afternoon and they tattoo until 2:00 in the morning. “And that’s where I learned to make money,” Thomas explains.

Zeke, however, had learned this lesson for himself in Hawaii, back in 1961. Recently fired from his job, he hears of an opportunity with Sailor Jerry (Norman Keith Collins). He promptly buys some Hawaiian shirts, packs his suitcase, and makes his way to the islands. Little does he know what he’ll find: Jerry’s shop is down on the skids. There’s puke on the street and junkies shooting up. He’s depressed, and ready to go home, but chooses to sit through a shift. For the rest of the day the two pound out images of tiny bulldogs with hats on. By the end of it, he’s made $1,700, and Sailor Jerry is up $5,000. After that, it doesn’t seem so bad.

Seeking Understanding of the Craft

As we enter his shop (a few blocks away) Lockhart’s chihuahua, Snook, races across the room to greet us. Aside from this one small exception, the shop looks exactly like it should. It’s clean and utilitarian, with a mixture of tattoo art, tools, and ephemera blanketing every wall. This isn’t by accident, or without due consideration. While others have taken different approaches, Lockhart feels this is what a tattoo shop is supposed to be—and that’s what he wants to deliver to visitors.

The flash (letter sized sheets of paper, with tattoo designs printed on them) on the walls is highly varied. Some sheets date back over 100 years. It’s easy to get lost in these walls, purely from a visual appreciation standpoint—none-to-mention what they say about those who commit to these forms for the rest of their lives. The older artwork is beautiful and considered, whereas the newer ones sometimes feel more like stickers or badges. While the former are clearly representative of an art form, the latter remind me that this is also very much a business.

Nevertheless, Lockhart seems to be a purist. He won’t take on a job that requires him to tattoo gang symbols or names of lovers. He campaigns to put an end to harmful toxins found in certain tattooing inks, and talks disparagingly about the poor quality of some low-cost offshore materials that are making their way into the marketplace. He’s equally concerned about how some shops are simply fronts for illicit activities, and how this damages the craft.

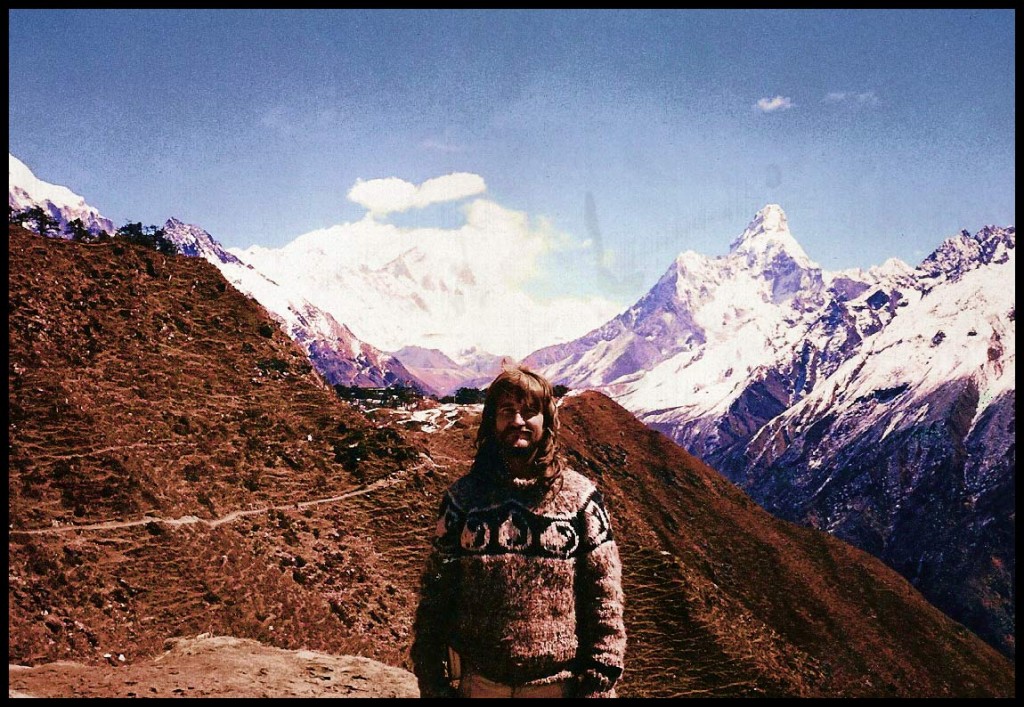

Lockhart’s interest in the tattoo may have been sparked at Yurkew’s convention, but his quest to understand it is longer and takes him further afar. He makes, what he refers to as, pilgrimages to artists in Los Angeles and San Francisco. He’s riveted by how they are defining their own style, while drawing upon the Japanese methods introduced to the west by Sailor Jerry. He learns a little something from these artists and, along the way, a couple of them start inking what will eventually become his full body tattoo.

He travels to Yokohama, Japan, where he meets Yoshito Nakano (later known as Horiyoshi III). When presented with the offer, this up and coming artist sees an opportunity in outfitting Lockhart with a kimono tattoo—hand tapped in the traditional fashion with a stick, and up to 40 needles attached. He knows this work will travel back to the west with his subject, and understands what this may represent for his reputation. During that long process, Thomas learns even more about the craft, and the two become friends.

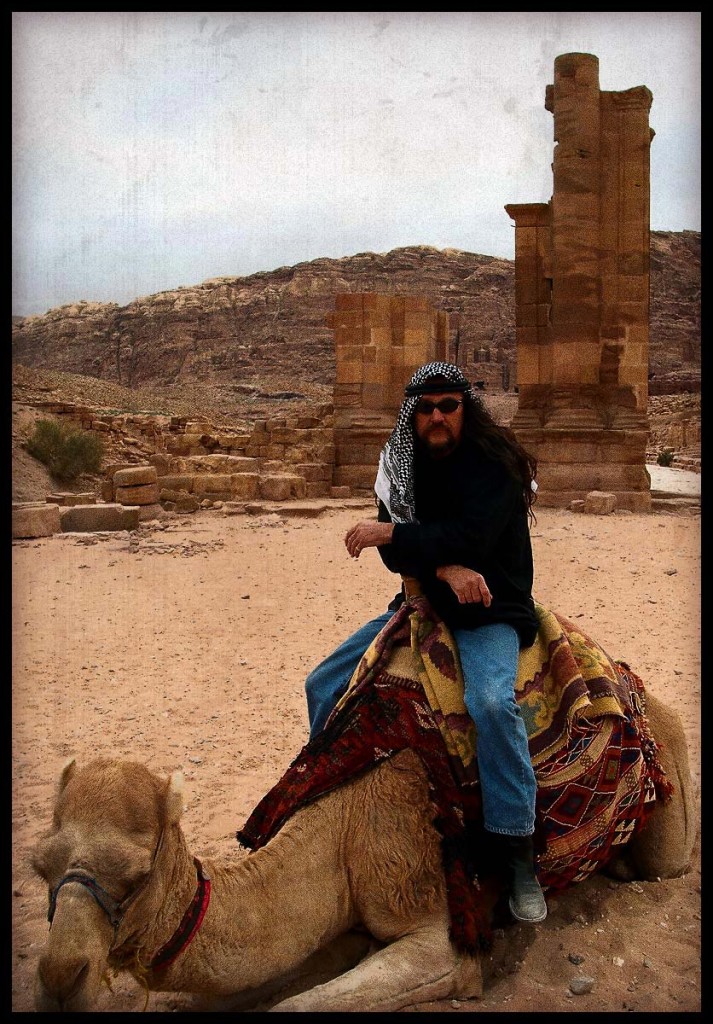

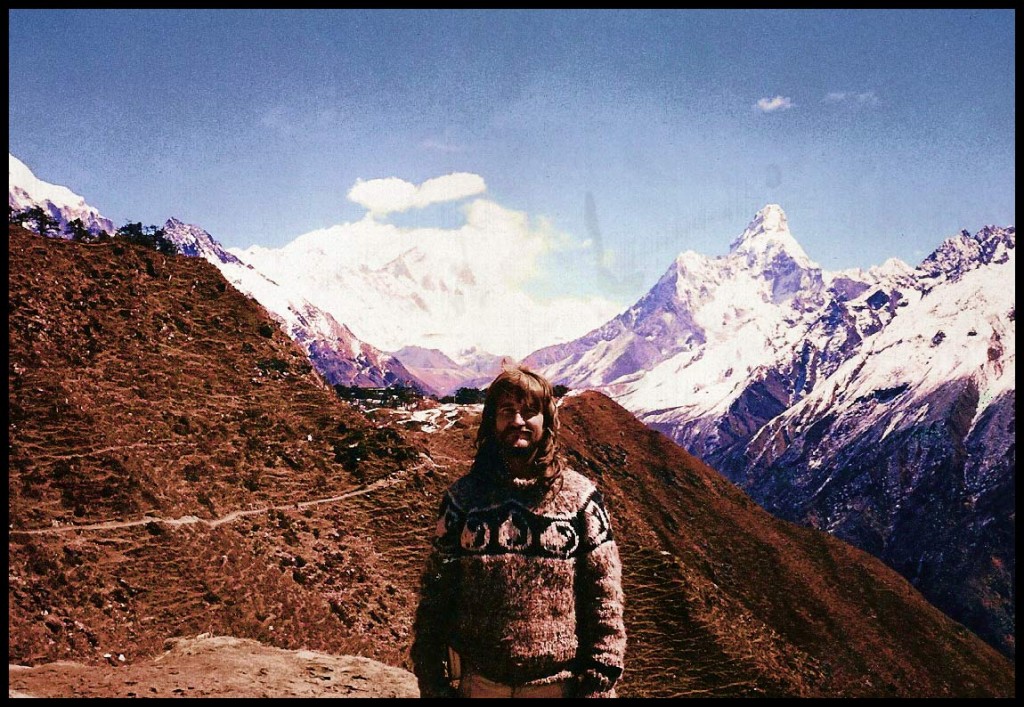

This, however, just scratches the surface of his travels. Wherever he can learn more about his craft, he goes. In a respect, it’s as though tattooing is a doorway, which leads him to explore the world. When prompted, he rattles off a long lists of places he’s been, “Japan, South Seas, Europe, South America, Africa, Canary Islands, the States, New Zealand…” he shrugs his shoulders and concludes, “that’s about it.” (As the conversation continues, I realize that this only scratches the surface.)

A Passage Into the Valley of the Headhunters

In 1979, after scratching in various locals for 2 or 3 years, he starts a shop on Davie Street. He runs it in that same spot for nearly 30 years. It’s one of the busier streets in the area, and one that undergoes substantial gentrification in the 1990s. Eventually, he’ll trade this location for one closer to Commercial Drive, where rents are more affordable, and the parking isn’t such a nuisance for his customers.

While still in his Davie Street shop, he’s met by producer/writer Vince Hemingson, who harbors a growing fascination with tattoos. Thomas soon draws him into discussions on tattoo history, largely concentrated on those practicing in remote parts of Borneo. He talks about the significance of the tattoos of the Iban, whose markings were long treated as both a means of gaining strength and support from the spirit world—alongside serving a certain functional purpose in attracting potential mates. Due to Western influence, however, this artwork and history may soon fade completely, becoming lost to future generations of Iban.

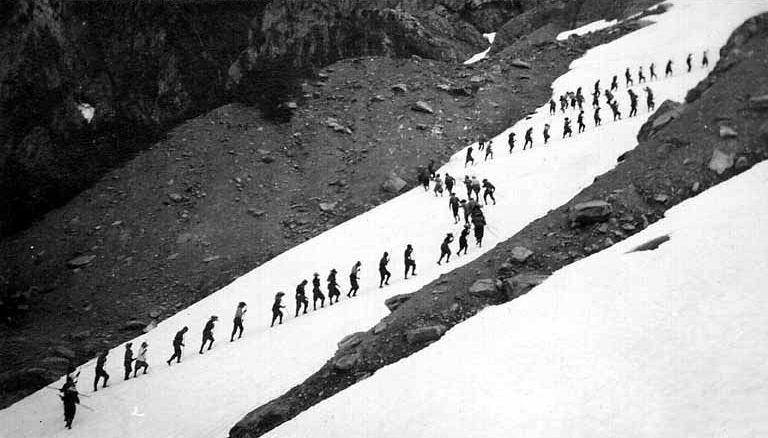

Their shared fascination, coupled with a desire to tell this story, gets them thinking about creating a documentary concentrated on the topic. They head out, trying to drum up interest, soon finding a partner in National Geographic. With a small budget in hand, they make their way down the Skrang River (once known as the River of Death) to document these vanishing tattoo practices, and better understand the meaning of these tattoos to their people.

For three weeks, they bear blistering heat and nearly 100 per cent humidity, while sleeping on wooden floors, in longhouses shared by up to 120 people. This, of course, is the tough part. The rewards come in the hospitality of the Iban people, their willingness to share stories and discuss the relevance of their body art, and the opportunity to meet a couple of elders—whose insights are not, for much longer, of this world. They learn how for the Iban, the skull is seen to contain one’s soul, and how warriors would collect them to gain the strength of many. They also uncover that in battle, tattoos were believed to serve as armor against even the machine gun fire of modernized armies. You can view the first part of the documentary here:

While I’m fascinated by what they’re able to see and take in, the practicalities of their travel seems overwhelming to me. On this particular trip, they need to make their way down gnarly rivers, whose turbid water camouflages stones that threaten to disembowel their boats and toss them into fast-moving currents—containing rather threatening looking alligators. (On other journeys, like one on the Amazon, he finds a monkey hand floating in his soup.) Personally, I don’t have the guts to go to these places. That, however, doesn’t change how fun it is to listen to his stories.

On the Road in Your 50s

In spite of his adventurous spirit, Lockhart isn’t a young man. When we first met, twenty years ago, he seemed a little harder, perhaps even standoffish. I was intimidated by him then, and was expecting to be so today. Maybe I’m just older and reading him differently, but he now seems more open—even chatty. He works through a bowl of wonton soup, and a few glasses of wine. Even though I’m the one who asked for his time today, he insists upon buying my lunch, waving his hand dismissively, “put away your little credit card.” He then teases our waitress who seems to know him well. I’m left with the impression that he has lunch here every day.

He once maintained a boat in False Creek that served as an apartment of sorts for traveling artists who would work in his studio. His interest in working with others has waned, though, and he now prefers to practice his craft on his own. Most of his projects are larger in scale, and only a few of his customers come to him off the street as casual walk-ins.

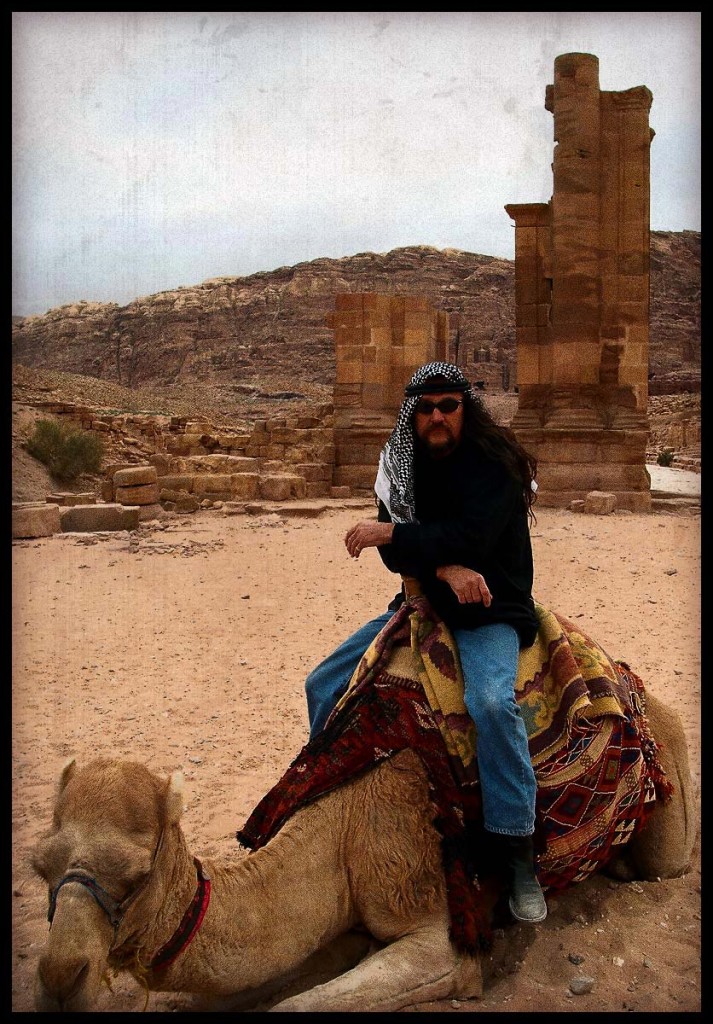

Still keen to travel, he acknowledges that it’s different for him than it once was. For the past decade, he’s become more accustomed to being in the company of his wife, Sharon, who he describes as very easy to get along with. His last trip alone was to Jordan and Israel; it was a dismal experience. He felt very little connection with fellow travelers, particularly because most on such trips are in their late teens to early thirties. Hostels, he acknowledges, are less comfortable as one grows older, and many staying in such places find his snoring bothersome. This hasn’t minimized his deep-seated wanderlust, but it does seem that few others in his age-bracket are quite as prepared for the kind of exploration he enjoys.

Tomorrow, I’ll head back to my agency, where my day will pass in a flurry of email, meetings, and scheduling conflicts. Thomas, on the other hand, will return to his tranquil shop, where one of his 30, or so, regulars will come back to him to continue working on the sleeves and backs he’s known for (these are long-term commitments, often lasting around 20 years).

Come January, I’ll be scrambling to drum up work, or finish projects that are running behind; he’ll be at his little place in the Dominican, or traveling to Turkey—a place he desperately wants to explore.

Interesting People Always Seem Interested

What strikes me most, throughout our discussion, is how truly situated Lockhart seems to be in this world. He spends a few days a week working on the tree farm his grandfather started cultivating in the 1940s. He’s built his own plane. He understands the differences between Sunnis and Shiites; does work for schools in developing countries; is adept in the dynamics of Vancouver politics… and he’s not averse to calling out some of them for things he disagrees with. (He admits that while he enjoys drinking with them, few appreciate such prodding.)

Nevertheless, there he is: the real deal. Quintessentially curious, often tangential, and seemingly unafraid of the constraints that people like me tend to feel blanketed in. Our conversation leaves me feeling like a beginner: provincial and ignorant of the bigger world that surrounds me. I can talk up a storm about integrating social media in a campaign, or the means of aligning brands, but this largely feels like subterfuge: modern day constructs with little connection to anything real.

I explain that I’m unclear on exactly what I’m going to pull out of our talk. It went all over the place, and I don’t know how to properly convey his story. He gives me a fist bump and tells me that I should take whatever I’d like from the meeting, and write what I want. “You’ve led quite a life,” I note, as we part ways. There’s a momentary pause, before he responds, “Hey—it isn’t over, yet.”

To learn more about the history of tattooing, visit Lockhart’s the Tattoo Museum; to meet the man himself, and perhaps get inked, visit West Coast Tattoo.